Every Technological Change has Unintended Consequences

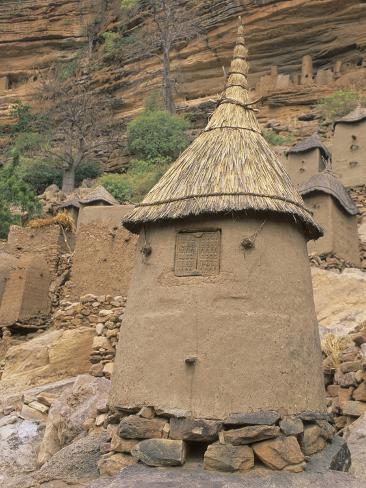

Prologue: Agricuture

The practice that gave us civilization, also challenged us as individuals:

The practice that gave us civilization, also challenged us as individuals:

Eleven thousand years ago, absolutely no one grew their own food. Instead they lived off of wild game, fish, and plants. Today only a tiny handful of people continue to live this way. Instead we live off of food that we cultivate deliberately or that someone else cultivates for us. Indeed, by the time everyone in this room is dead, there will probably be no primarily hunting and gathering cultures left. Their members will have dispersed and been assimilated by agricultural cultures.

Origins of Agriculture:

Origins of Agriculture:

Why did this change occur? After all, humans had done nicely as hunter/gatherers for many millenia.

A synthesis of current anthropological, archeological, and historical data that suggests something like this.

Advantages of food production:

- Manure for fertilizer

- Animal muscle strength for plowing.

- Chieftans and kings

- Priests

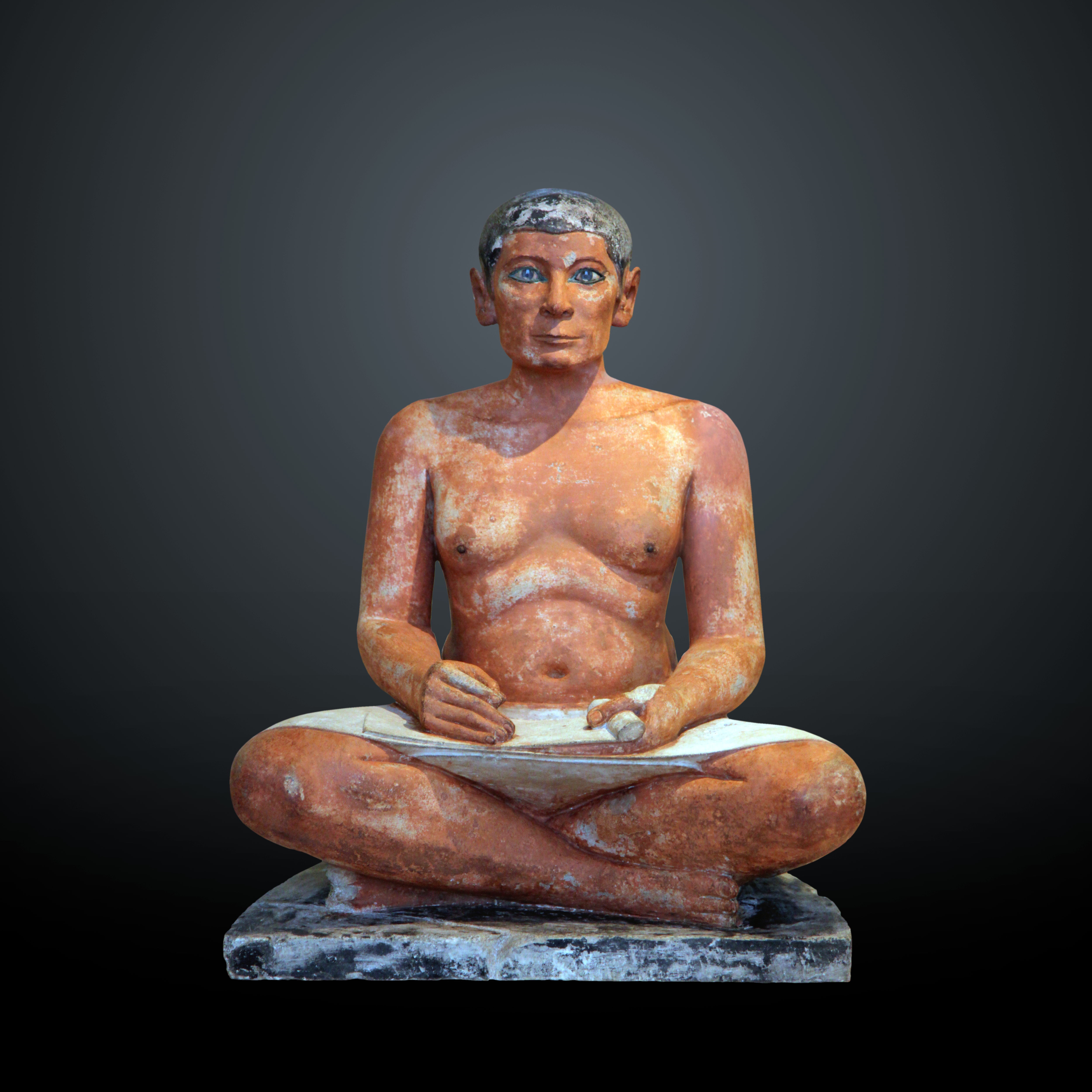

- Specialist craftsmen

- Scribes and Bureaucrats

- Soldiers

- Increased human fecundity: Hunter-gatherers must carry their children with them when shifting camp. Thus, a woman may have no more than one child too small to keep up on its own. Between lactational amenorrhea, the effects of a low-carbohydrate "wild" diet, and other measures, births to hunter-gatherers are typically spaced about four years apart. Farmers, in contrast, can support as many children as they can feed, and a high-carbohydrate diet facilitates frequent pregnancies.

Concentration of useful biomass: Most plants (99.9 %) are "weeds" - useless to humans. To have enough useful ones, hunter gatherers must control large areas with diverse species. Farmers can simply turn a small area over to a monoculture of the plants they need.

Opportunity to domesticate livestock: Hunter-gatherers frequently move their camps. This eliminates the possibility of keeping large animals captive long enough to institute captive breeding. Farmers, in contrast, were responsible for major domestications of large herbivores. (Dogs, domesticated before the invention of agriculture, were a different story.)

Opportunity to domesticate livestock: Hunter-gatherers frequently move their camps. This eliminates the possibility of keeping large animals captive long enough to institute captive breeding. Farmers, in contrast, were responsible for major domestications of large herbivores. (Dogs, domesticated before the invention of agriculture, were a different story.)

Use of livestock in agriculture:

Food storage: Hunter-gatherers have no effective means of long-term food storage. By favoring seed crops, farmers harvest the part of the plant that is capable of prolonged dormancy in the wild. Granaries give humans a buffer against unpredictable food shortages.

Food storage: Hunter-gatherers have no effective means of long-term food storage. By favoring seed crops, farmers harvest the part of the plant that is capable of prolonged dormancy in the wild. Granaries give humans a buffer against unpredictable food shortages.

Division of labor: Once you have the ability to store food, it becomes possible to feed individuals who don't actual produce their own. Thus:

Division of labor: Once you have the ability to store food, it becomes possible to feed individuals who don't actual produce their own. Thus:

But the big one:

But the big one:

The drawback of agriculture

The drawback of agriculture

People raised on a monoculture of a small number of high-carbohydrate staples (wheat, rice, manioc, corn potatoes, or whatever grew locally) were significantly malnourished compared to hunter-gatherers with a varied diet. Consider:

- In any given location, average stature diminished roughly 6 in. when societies adopted agriculture.

- Nutrition-based diseases such as tooth decay became common

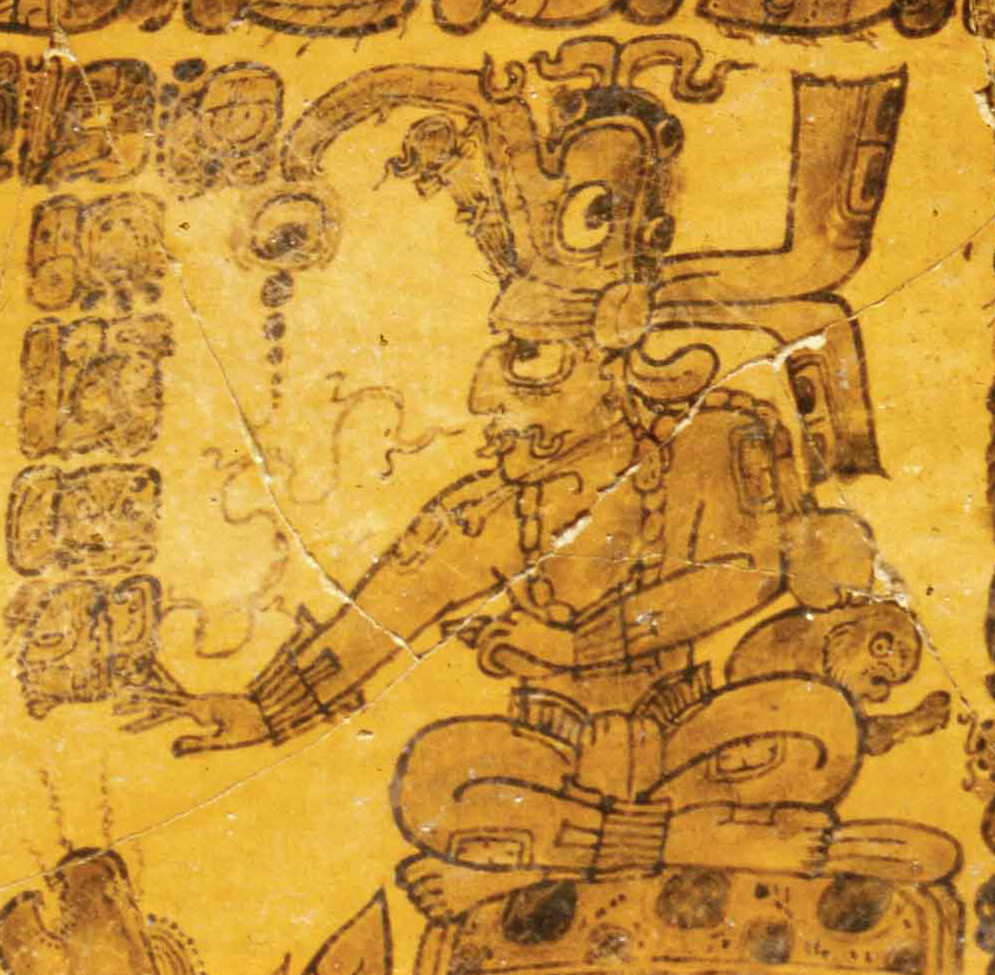

- Among the classic Maya (whose ancestors had adopted agriculture ~ 5000 years earlier), members of the nobility were on average ~ 6 in. taller than commoners.

Agriculture, thus, not only has immediate benefits, cultures that adopt it soon find that they can't back away from it without:

Agriculture, thus, not only has immediate benefits, cultures that adopt it soon find that they can't back away from it without:

- rising against their ruling class

- condemning much of their newly increased population to starvation.

The global economy does not restore everything to the way it was:

But we obviously don't suffer from these problems: What has changed?

That requires us to consider a second great invention: Sailing.

Predynastic Egypt: Boat under sail 3500 BCE

- Necessary because vessels needed security to avoid pirates and other hazards regardless of wind conditions.

- Adequate because no sailing vessel was so big that it couldn't be propelled by oars when the wind failed.

- Relatively defenseless cargo ships could sail without fear of attack

- Society absolutely depended on large scale shipping to power its economy and to sustain its population. Indeed, the annual arrival of the large (up to 1,200 tons displacement, similar to modern Simon Bolivar) grain ships (right) from Egypt (an agricultural exporter) was of crucial importance to Italian cities that could no longer feed themselves without imported staples.

The fall of the Roman Empire set maritime progress back for centuries, but by the fifteenth century European and Chinese (right) ships were making unprecedented voyages of discovery in ships that rivaled their Roman predecessors. Within a century, ships were transporting goods across the Atlantic and Pacific with a degree of security and reliability like the ancient Mediterranean. The result was a global economy in which:

- Silver from Peru transported in Spanish ships could pay for Chinese products to be sold in England.

- Food staples that had previously been regional were distributed world wide (E.G. Andean potatoes became established in Europe.)

The result: A gradual increase in human health. At first, exotic crops became established in new countries, but by the mid 19th century, actual perishable produce could be shipped between continents. A global food economy enabled most of us to return to the kind of healthy diet for which our bodies evolved. (Stature, at right, is a good first-order proxy.)

The result: A gradual increase in human health. At first, exotic crops became established in new countries, but by the mid 19th century, actual perishable produce could be shipped between continents. A global food economy enabled most of us to return to the kind of healthy diet for which our bodies evolved. (Stature, at right, is a good first-order proxy.)

Problem solved? Perhaps, but the solution spawned more problems...

Future shock I: Global economy transforms global ecology:

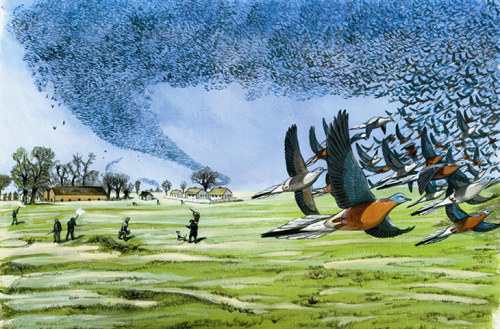

The Columbian Exchange Starting in 1492, entire suites of exotic plants and animals were exchanged between the New and Old Worlds, seriously disrupting ecosystems. The effects could be subtle but started immediately. For example, immense flocks of passenger pigeons (right) witnessed during the nineteenth century apparently didn't occur prior to 1492 (judging from archeological remains of Indian kitchen refuse.) Evidently some change wrought by the Columbian Exchange released them from their historic ecological limits.

The Columbian Exchange Starting in 1492, entire suites of exotic plants and animals were exchanged between the New and Old Worlds, seriously disrupting ecosystems. The effects could be subtle but started immediately. For example, immense flocks of passenger pigeons (right) witnessed during the nineteenth century apparently didn't occur prior to 1492 (judging from archeological remains of Indian kitchen refuse.) Evidently some change wrought by the Columbian Exchange released them from their historic ecological limits.

Other changes were more direct: 17th through 19th centuries - Large-scale hunting and extinctions as Europeans colonized the world, introducing more potent methods of hunting and converting large regions to agriculture. E.G. the:

- Dodo (1662) - Flightless pigeon of Mauritius: killed to provision ships, interaction with introduced species, habitat destruction

- Steller's sea cow (1768) - Kelp-eaqting sea cow of the northern Pacific: hunted to provision ships, blubber used in whale oil trade.

- Great Auk (1844) - killed to provision ships.

- Passenger pigeon - (1914) killed to satisfy demand for game and feathers (for use in millinary)

- Heath hen (1932) - combination of hunting, habitat destruction, interaction with introduced species, and bad luck.

Future shock II: Global commerce leads to alcoholism, spouse abuse, and crime.

Brandy: The technique of distilling liquor was known from classical antiquity but it was only with the dawn of the global economy in the 16th century that this difficult procedure was applied on a large scale. What had changed?

Brandy: The technique of distilling liquor was known from classical antiquity but it was only with the dawn of the global economy in the 16th century that this difficult procedure was applied on a large scale. What had changed?

- Colonial powers had to ship large quantities of wine to their colonies

- Large amounts of wine now being shipped across national borders were being taxed per unit volume.

Alas, although people in many regions have been drinking beer and wine for millenia, and have evolved resistance to its most dangerous effects, no population has had time to evolve tolerance for concentrated alcoholic beverages. As the global economy provided access to distilled spirits, their public health effects, including increased alcoholism, became more intense.

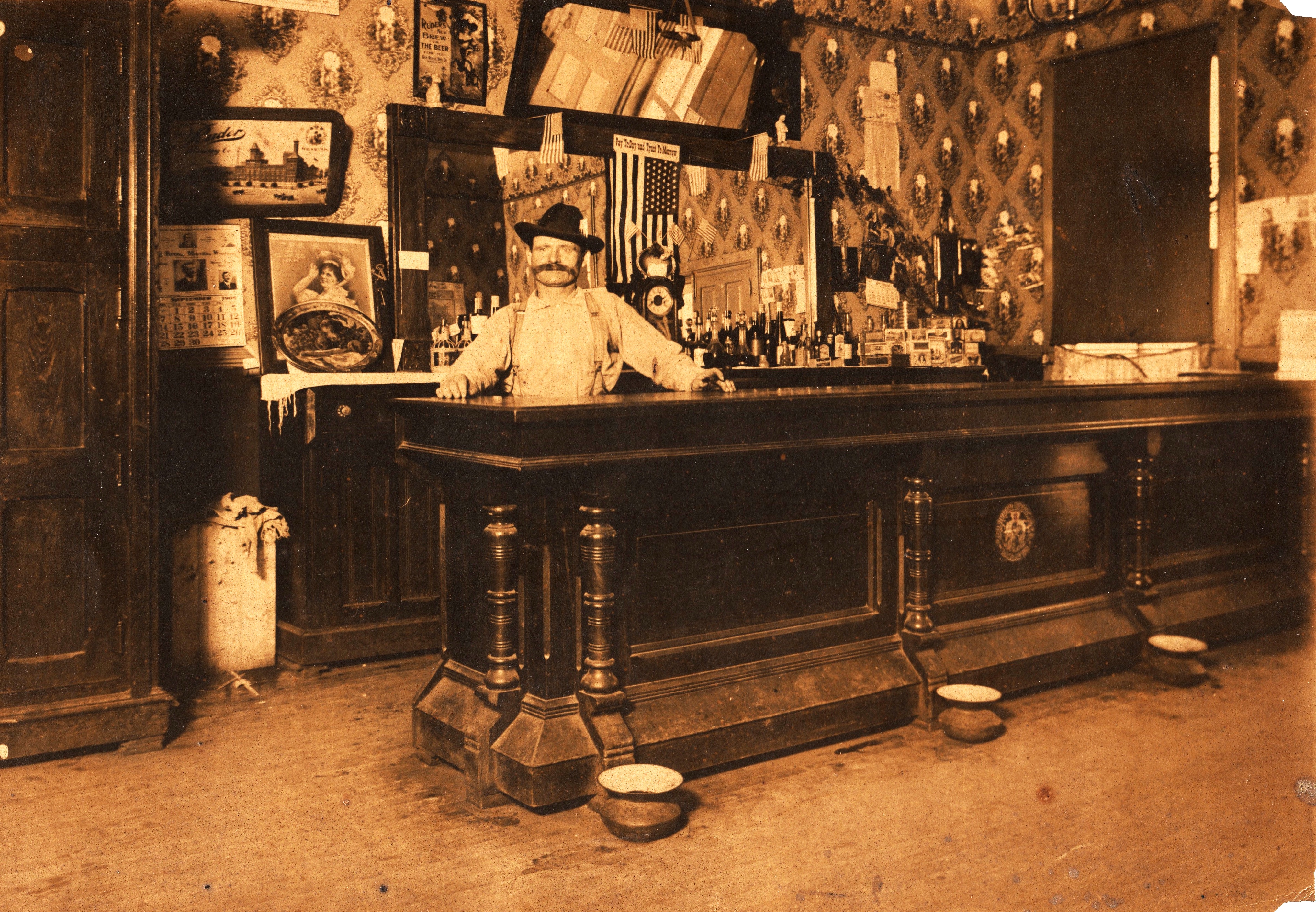

Alcoholism as a women's rights issue: In the 18th and 19th century United States, this problem was compounded by two social institutions:

Alcoholism as a women's rights issue: In the 18th and 19th century United States, this problem was compounded by two social institutions:

- Saloons: (Right from Thomas/Kruger family ancestry) Drinking establishments patronized by men, in which drinking was associated with machismo and male camaraderie.

- Laws specifying that the income of married women belonged to their husbands.

Temperance: In a society where the legal empowerment of women was still far off, the obvious solution seemed to be to enforce good spousal behavior by limiting access to alcohol and shutting down saloons - the temperance movement, pursued by organizations like the Women's Christian Temperance Union. In fact, many activists who would later figure in the women's suffrage movement got their initiation in the temperance movement. Additional complexities included:

- The association of heavy drinking with immigrant communities, especially German Americans who dominated the brewing trade.

- The cultural divide between rural and urban society.

- The federal government's dependence on taxes on liquor sales for revenue

Prohibition: The issue came to a head in nineteen-teens when:

Prohibition: The issue came to a head in nineteen-teens when:

- it became clear that a majority of both parties supported it

- the 16th amendment created the federal income tax

- the US entered WWI, demolishing the influence of German American brewers.

- The loss of jobs in brewing and related trades.

- The rise of a lucrative organized criminal trade in alcohol (primarily the soft stuff like beer and wine that had long been an accepted part of culture) with financial and political resources that totally outclassed the efforts of law enforcement to deal with it. (Despite the occasional success of law-men like Eliot Ness.)

- Increasing public disrespect for the rule of law.

- Fundamental changes in the ways men and women socialized. (Saloons were gone, and bars (starting with illegal speakeasys) provided places for men and women to drink together.)

Future shock III: Coal power and empires - the means dictate the purpose

Why do we even have empires? Starting in the 15th century, European powers began to develop colonial empires. Exact reasons varied but they usually centered on:

Why do we even have empires? Starting in the 15th century, European powers began to develop colonial empires. Exact reasons varied but they usually centered on:

- Ideology - E.G. spreading the "true faith" to the less fortunate.

- Raw materials - Colonies provided a source of raw materials for manufacture and trade. (Metals, crops, spices, forest products, ivory, etc.)

- Trade - Colonies provided a guaranteed captive market for a great power's exports.

- Lebensraum - a settling ground for the power's unsettled population.

The global economy thrives on security. For commercial vessels, that security was, for centuries, provided by sailing warships bristling with heavy cannons. The warships themselves had to provide their own security. That meant being heavily armed with cannons that could fire at an enemy approaching from any direction. Necessary because one couldn't depend on the wind. Sailing navies longed to break free of their dependence on the wind like their predecessors in lighter oar-driven warships had been prior to the age of gunpowder. Then it happened.

The steam engine steam engines became available as an auxiliary power source, navies scrambled to use them. By the time of the Civil War, a first rate warship like the CSS Alabama (right) would cruise under sail but fight, or maneuver in port under steam power that turned a propeller. For sea-going commercial vessels that could expect tug-boat service in port and didn't need to be weighed-down by a steam engine, pure sail remained the standard.

The steam engine steam engines became available as an auxiliary power source, navies scrambled to use them. By the time of the Civil War, a first rate warship like the CSS Alabama (right) would cruise under sail but fight, or maneuver in port under steam power that turned a propeller. For sea-going commercial vessels that could expect tug-boat service in port and didn't need to be weighed-down by a steam engine, pure sail remained the standard.

But surprise - steam engines need fuel: In the mid-19th century, pure steamships were limited in range because of their need for fuel, and were used near the coast and on rivers. Still, the deployment of ironclad steam warships during the Civil War got navies thinking about the desirability of ocean-going steam ironclads.

But surprise - steam engines need fuel: In the mid-19th century, pure steamships were limited in range because of their need for fuel, and were used near the coast and on rivers. Still, the deployment of ironclad steam warships during the Civil War got navies thinking about the desirability of ocean-going steam ironclads.

The problem: Steam warships consumed prodigious amounts of coal and needed frequent resupply. The first ocean-going ironclad crossed the Atlantic in 1864, but such a ship could do little upon arrival until refueled. Alas, as armor and guns became more powerful, warships with sailing rigging were increasingly vulnerable, but switching navies over to steam power would require nations to develop global networks of well defended fueling stations. The HMS Captain 1869 (right) represents the last serious attempt by any navy to build a fully modern sailing warship. Its innovative design separated the gun turrets and rigging on separate decks. Unfortunately its design and construction had been poorly supervised and it was heavier and had a higher center of gravity than planned. It capsized and sank in heavy weather during its first year of operation. This event did for the image of sailing warships what the crash of the Hindenburg did for that of airships. The global powers took the steam plunge.

Power warships and the price of strength: By the 20th century, naval ships (E.G., the HMS Dreadnought - right) were powerful steam-powered steel-hulled monsters. But there was a price for this modernity. Consider: In WWII, the Bismark, one of the most powerful battleships ever built, on its first combat mission, was severely limited in its operational scope and ultimately trapped and destroyed because of its need to reach a friendly port for refueling. Compare that to the CSS Shenandoah, which was operating in the north Pacific when its crew learned of the end of the Civil War, then sailed non-stop and undetected by U.S. authorities to surrender to the British in Liverpool.

Power warships and the price of strength: By the 20th century, naval ships (E.G., the HMS Dreadnought - right) were powerful steam-powered steel-hulled monsters. But there was a price for this modernity. Consider: In WWII, the Bismark, one of the most powerful battleships ever built, on its first combat mission, was severely limited in its operational scope and ultimately trapped and destroyed because of its need to reach a friendly port for refueling. Compare that to the CSS Shenandoah, which was operating in the north Pacific when its crew learned of the end of the Civil War, then sailed non-stop and undetected by U.S. authorities to surrender to the British in Liverpool.

Game change: The biggest change was in the colonial powers' rationale for having colonies at all. Now their largest role was to provide a global network of fueling stations for their navies. Indeed, even when former colonies became independent during the 20th century, colonial powers tended to retain control of strategic bases.

Sailing commerce and security II: The switch to steam-powered warships didn't effect sailing commerce. Indeed, the Thomas W Lawson (right), the largest pure sailing vessel in history, was launched in 1902. As in the ancient Mediterranean, however, sail-propelled commerce required security. The breakdown of global security in World War I put an end to such vessels, which were very easy visible targets for steam warships and submarines. In response, freighters became steam or petroleum powered, for rapid passages and in WWII, to keep up with convoys.

Sailing commerce and security II: The switch to steam-powered warships didn't effect sailing commerce. Indeed, the Thomas W Lawson (right), the largest pure sailing vessel in history, was launched in 1902. As in the ancient Mediterranean, however, sail-propelled commerce required security. The breakdown of global security in World War I put an end to such vessels, which were very easy visible targets for steam warships and submarines. In response, freighters became steam or petroleum powered, for rapid passages and in WWII, to keep up with convoys.

Future shock IV: 20th century industry and "a woman's place."

Remember the women of the 19th century temperance movements? Many, including Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony, went on to campaign for women's suffrage. In 1919 women received the right to vote, however at the time of Merck's birth, most middle class women were home-makers of some stripe. That was despite:

Remember the women of the 19th century temperance movements? Many, including Elizabeth Stanton and Susan Anthony, went on to campaign for women's suffrage. In 1919 women received the right to vote, however at the time of Merck's birth, most middle class women were home-makers of some stripe. That was despite:

- the extensive entry of women into the workforce during the two world wars to fill temporary positions

- the repeal of laws barring them from careers and ownership of their income after marriage.

- Demonstrated that capitalist free enterprise was better at identifying society's needs than a planned economy.

- Show-cased American technical know-how.

That exhibition became the prop for the famous impromptu Kitchen Debates between US Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that began when Khrushchev, while being given a tour of the exhibit of a modern middle-class American home, prodded his host into a wide ranging debate about the relative merits of the US and Soviet systems. Khrushchev raised at least one point with some merit, pointing out that in the Soviet Union women were integrated more fully into public life and weren't patronized by a system that required them to be pampered housewives.

In fact, as of 1959:

- American women's professional opportunities were quite limited

- Those who pursued careers were often unmarried

- Married women who worked were presumed to be doing so out of severe financial need.

- But many women who lived through that era will tell you that they were actually bored as housewives.

During the 1960s and 70s, matters came to a head:

- Reliable birth-control pills became available (and were legal in all states by 1970). Thus, a home-maker could, for the first time ever, choose when she wanted to have a baby and when she prefered to be pursuing a career.

- Other contemporary social upheavals created a general sense that all social assumptions were open to question.

Postscript: The really big future shock

SGC exists to address what may be the biggest unintended consequence of our era: Anthropogenic Global Climate Change. This is the unintended result of the well-intentioned efforts of industry (capitalist and planned) to provide for society's needs. Our efforts to mitigate it and adapt to it will involve new technologies with their own inevitable future shocks. Some harbingers:

- Patterns of political influence will change: Authors Galbraith and Price describe the growth of Texas, ground-zero of the petroleum industry, into the nations number one producer of wind power in a new book. How will this fact effect the political influence of the petroleum industry?

- New energy technologies must mature Wind power might be the wave of the near future, but what can we say about an industry that must occasionally pay people to buy its product because of oversupply? We await the development of a smart grid that can transmit wind energy efficiently.

- Patterns of dependence on imports will change: Hawaii, long dependent on imports of fossil fuels, is a leader in clean energy alternatives. Major wind farms are already in operation, and a 2010 study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory projects that Hawaii has the capacity to supply 100% of its energy needs using wind power.

As you pursue your search for solutions, try to anticipate the unanticipated effects they will invoke.