"The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward." -- Winston Churchill, 1944

"An evolutionary perspective of our place in the history of the earth reminds us that Homo sapiens sapiens has occupied the planet for the tiniest fraction of that planet's four and a half thousand million years of existence. In many ways we are a biological accident, the product of countless propitious circumstances. As we peer back through the fossil record, through layer upon layer of long-extinct species, many of which thrived far longer than the human species is ever likely to do, we are reminded of our mortality as a species. There is no law that declares the human animal to be different, as seen in this broad biological perspective, from any other animal. There is no law that declares the human species to be immortal." -- Richard E. Leakey & Roger A. Lewis. (1977), Origins: What New Discoveries Reveal About the Emergence of Our Species and Its Possible Future.

BIG QUESTIONS: How do we balance public and private interests in fossil specimens? How do scientists get their information out to the public?

What Good is a Fossil Record?

That is to say, what benefit does society receive from the existence of fossils of the ancient world? There are many of them that are scientific:

But are there any pragmatic benefits? YES!

And some benefits are even aesthetic:

This final lecture we'll look at some of these big issues of the fossil record in society: who owns the fossil record? And where we should go to get information from the fossil record. But first, we'll look at people who misrepresent the fossil record.

All the science discussed throughout the course is predicated on the idea that fossils are the authentic record of life in the past. Our disagreements about them would be differences of interpretation, but we accepted that the bones, teeth, wood, leaves, shells, etc. are the remains of REAL bones, teeth, wood, leaves, shells, etc. But what happens when they aren't? Or aren't in their original association? What happens when people--for whatever reason--fake the fossil record? Although they are relatively rare, there are (sadly) many notable examples. And these illuminate some of the different motives behind making faux fossils.

There is a continuous gradation between well-established scientific ideas; ideas which are not as strongly supported but not currently rejected by current evidence; ideas on the fringes of science which are less well-supported than the main current of the field; and actual outright pseudoscience. As such, a precise definition of pseudoscience is difficult. The astronomer and science popularizer Carl Sagan suggested the following: that pseudoscientific ideas "purport to use the methods and findings of science, while in fact they are faithless to its nature--often because they are based on insufficient evidence or because they ignore clues that point the other way."

There are many cases where people make pseudoscientific--or at least poorly supported--claims about fossil material, often because they are simply unfamiliar with the details of the science and only have a superficial appreciation of how paleontology and geology work. For instance, British cell biologist and science writer Brian Ford has recently written a book on, and is on a speaking tour about, his idea that all dinosaurs were strictly aquatic and unable to move around on land. Although some 19th Century and early 20th Century paleontologists considered that at least the giant sauropods were mostly aquatic, that idea was long since overturned by functional anatomy, ichnology, and paleoenvironmental analysis. So the "strictly aquatic dinosaurs" hypothesis is not supported by the evidence.

In other cases, the idea is pseudoscientific now but was once a valid idea: the supporter simply refuses to acknowledge the falsification of their once-potentially-possible hypothesis. A classic example of this is the "Birds are not dinosaurs" (BAND) proponents discussed previously.

A more extreme example is pseudoscientific ideas is supporting the non-parsimonious, non-consilient idea and say that the reason it is rejected is a conspiracy by "mainstream science." One such example from the evolutionary realm is the "Aquatic Ape Hypothesis", the idea that somewhere between the split between humans and chimps and the rise of Homo sapiens that the homininan lineage went through a primarily aquatic phase. (To be fair, as discussed earlier, H. sapiens does seem to have gotten more of our food from the water than other related primates, but through nets and fishhooks and the like.) While this idea does not contradict natural laws (neither does the BAND or the fully aquatic dinosaur idea), it is not the simplest solution for the morphological, ichnological, and sedimentological data. Indeed, had humans gone through an aquatic phase (in which they lived in D-World!), the record of early stem-humans would be expected to be a lot more complete than it is! Paleoanthropologists do not reject the Aquatic Ape hypothesis due to some sort of vested interest; they do so because better evidence points to a different (fully terrestrial) solution.

Farther from reality still are examples of pareidolia: seeing things that aren't actually there. The human mind naturally sees shapes and patterns even when they aren't there: this had selective advantages in the past (individuals acting on the false belief that there is a predator at the watering hole were more likely to survive and have offspring than those not acting on the false belief that there ISN'T one when there is...) (By the way, we are VERY likely to see faces in places where there aren't any really faces!)

Some of the most spectacular paleontological pseudosciences came from pareidolia. In the 1970s and 1980s carbonate petrologist Chonosuke Okamura began to describe a number of amazing fossils from limestone thin sections from the Silurian Period. These included the first ever Silurian bird, the first Silurian camel, the first Silurian dinosaur, and more. Not only were these hundreds of millions of years older than these groups should have been, the were all microscopic!! His work eventually found microsopic Silurian people, including princesses. Since these were really just shapes he was seeing rather than real fossils, the peer reviewed literature did not publish his findings. So at his own expense he published his own Original Reports of the Okamura Fossil Laboratory, and sent copies to many paleontological libraries around the world (including the Smithsonian.)

Another famous case of paleontological pareidolic pseudoscience (also, coincidentally, from carbonate geology) was the work of micropaleontologist Randolph Kirkpatrick. He had a productive career in science, but he developed a radical new hypothesis outside of these publications. He had long studied nummulitids: a distinctive group of gigantic macroscopic foraminiferans common in the Eocene to Miocene. Their distinctiveness makes them important index fossils for those epochs.

But where most paleontologists found nummulitids only in limestones, Kirkpatrick would see them in sand grains (even though sand grains are much smaller than nummulitids!!), in volcanic and plutonic igneous rocks, and even in diamond and meteorites!! He developed a new model of how rocks formed, which he published as The Nummulosphere: an account of the Organic Origin of so-called Igneous Rocks and Abyssal Red Clays. In this he explained that ALL rocks were actually derived directly from nummulitids. (Because he saw nummulitids in meteorites he had to conclude that those rocks didn't come from space, because he thought that the idea that there was life in space was just too crazy!)

One of the most commonly head pseudoscience is the prehistoric survivor paradigm: the idea that non-avian dinosaurs, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, Basilosaurus, and more all survive in the modern world and are the source of legends and tales of dragons, of the Loch Ness monster, of the ropen, of sea serpents, and so forth. It is true that sometimes creatures once thought extinct turn out to be alive. The archetype of this are coelacanths: fish common in the late Paleozoic and throughout the Mesozoic but apparently died out at the K/Pg, only to turn up alive in the Indian Ocean. Yes, a genus of coelacanth does still live: but that doesn't mean that EVERY well-loved ancient form still lives! In order to demonstrate that one needs the actual physical evidence of it.

The most widespread and politically-influential pseudoscience about paleontology and related fields is evolution denialism (traditionally branded as "creationism" or "creation science", and more recently as "intelligent design theory".)

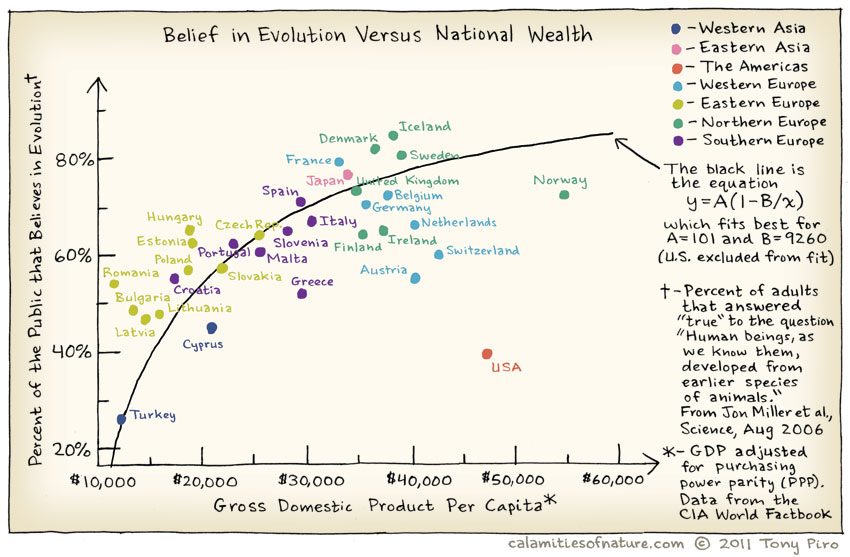

The above data is from the 2005 study by John Miller et al. As you can note, America ranks very far behind all other industrialized Western nations included, and just ahead of Turkey. Taking these data and plotting them against a measure of national wealth, we see that the US really is an outlier compared to other rich nations:

Why would people reject evolution anyway, particular in nations with an excellent fossil record and easy access to information by almost everyone?

All cultures of the world have had some idea about where the world, its life, and humans came from. For many the traditional idea is that some supernatural force of great power (a god or multiple gods) brought them into being. But they disagreed on details: which god; in what order; by what process; etc. For instance, Judaic chronologies traditionally held that Earth, Life, and Humanity were created over the course of the six day "Creation Week" described in Genesis, and that this was roughly six thousand years ago. Their neighboring cultures (Egyptians, Babylonians, Greeks) thought that the Earth was created many 10s of thousands of years ago. Some (the Maya, for instance) had even longer time scales, and Hindu cosmologies suggesting an infinitely old, repeating Universe (with a present incarnation many many billions of years old.) But many of these thought that the world was basically unchanged since the Dawn of Time, and did not consider any lineal connections of descent and ancestry among the species of the world.

During the Age of Enlightenment (18th and early 19th Centuries) there were many arguments for and against naturalistic views of how the Universe operates and came to be. For example, David Hume observed order arising from mindless mechanistic processes (snowflakes from water, crystals from solution, and so forth), and considered that an ordered world might likewise come out of similar type processes. In contrast, others argued that the apparent Design of the Universe implied a Designer. This was most famously (although not firstly) argued as the "Watchmaker Argument" of William Paley in his 1802 Natural Theology "Natural theology" was that branch of theology that attempted to understand the nature of the Divine not through revealed wisdom and scripture, but from study of the natural world. It had a long tradition in the West (e.g., medieval bestiaries, where the aspects of different animals were interpreted as moral lessons for Mankind.) Many of the early geologists and paleontologists were natural theologians: Linnaeus and Buckland and Agassiz and Lyell and others. But these naturalists also had to accept their discoveries of Earth vastly ancient beyond the chronologies of the Bible or the Classical World, with changing environmental conditions and inhabited by succession after succession of different life forms.

Of course, much of this came to a head with Darwin and Wallace's discovery of Natural Selection. They had discovered a mechanism to produce design without any need for outside influence: simply variation, heredity, and superfecundity.

The result of the publication of The Origin resulted in some rejection of Evolution by people within religious communities, but it was far from universal. Some religious thinkers were very much in support of Darwin and Wallace's new ideas, and some scientists rejected evolution (and more specifically the model of Natural Selection) at that time.

This sets the stage for the 20th and 21st Century American situation, and the rise of organized evolution deniers. But what do evolution deniers really believe? And why do they believe it? Despite what some might want to think, there is no simple dichotomy between "godless materialist evolutionists" and "Biblical-thumping fundamentalist Young Earth Creationists". In fact, there is a spectrum of beliefs (although not all of them are broadly represented in society at equal numbers by any means!). That said, the most influential and common evolution deniers are the Young Earth Creationists (YEC). They conceive of a world only thousands or maybe tens of thousands of years, a literal Biblical Flood and Noah's Ark, a literal Garden of Eden at the beginning, etc., etc. Looking just at the YECs, how wrong is their chronology? The actual age of the Earth at about 4.557 Gyr, but they claim a mere 6000 yrs. This is exactly proportional to claiming that the distance from Washington, DC to Los Angeles, CA (3690 km, or 2293 mi) is really only 4.86 m (16 feet)!! And in order to do this, one has to reject physics (nuclear decay, the speed of light, and so forth), astronomy, geology, chemistry: indeed, the whole corpus of modern Science.

Many have observed that the real reason for rejecting this aspect of science wasn't the science itself: it was the perceived implications of a material origin for humanity on the source of morality. They feel that if humans were not divinely created there could be no absolute morality dictated (literally) from On High, and that lacking such any sort of behavior might be condoned. (Of course this ignores millennia of work by ethical philosophers to find reasons for moral behavior outside of divine command, but that's outside the scope of this class!)

Additionally, this is part of what Carl Sagan called "The Great Demotions": the perception by some that as Science discovers the size and age of the Universe, Earth, and Life, that we seem more insignificant:

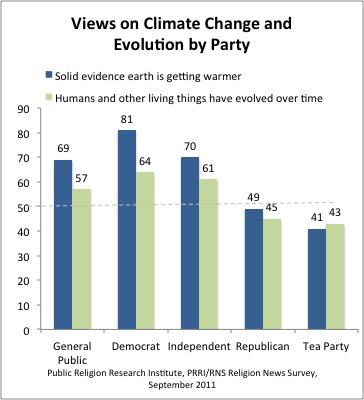

So why should we matter that some people fail to accept real things for personal reasons? What is the harm? In and of itself, that's all well and good. But part of the problem is that failure to think critically on one issue is generally linked with failure to think critically in most issues. In other words, pseudosciences tend to travel in packs. So those who reject evolution also tend to reject the reality of climate change, a phenomenon which effects all of us and which requires voting citizens to act:

Basically, once you accept that an ideology trumps evidence in one sphere, it becomes difficult to use your critical faculties in others. So the harm in rejecting well-supported discoveries like the antiquity of the Earth and the evolution of Life makes one susceptible to accepting untrue ideas, which will result in faulty decision making.

Some fossils obviously ARE commodities: coal, petroleum, chalk, diatomite, etc. And as such they are commercially bought and sold.

But what about the sort of fossils that this course focused on: the body and trace fossils of organisms as object?

In order to look into this, we need to consider the different types of people who search for fossils, and their motivations.

There are professional paleontologists: normally motivated by research, and normally employed by museums, universities, and other academic institutions. However, some might be employed by resource-management organizations (such as the US or state geological surveys; National Parks or Monuments; state parks; etc.): some of these may do research as well, but often they have the additional job of overseeing the protection of fossil sites and so forth. (And these jobs aren't mutually exclusive: the recently-retired State Paleontologist of Montana was also a Professor at Montana State University AND a curator of the Museum of the Rockies!) Professional paleontologists are the only group likely to develop major expeditions, and are the only group likely to prospect in formations that aren't yet known to produce lots of fossils: after all, discovery is our job! Given professionals tend to specialize on particular taxa (and thus might not be limited to working in just one region), but some work mostly on particular faunas or formations.

Another group is avocational collectors: hobbyists, enthusiasts, "amateurs" (in both the sense that the don't get paid to find fossils, and that they do it because they love it.) Avocational collectors are BY FAR the largest community. The tend to generate interest in fossils, and in Nature and Science, among the general public. Many important finds have been made by avocational collectors (which they often donate to museum collections). In general they tend mostly to prospect sites known to produce large quantities of common fossils (after all, they are more likely to do this for a day on the weekend, not a six-week expedition.)

The smallest group are commercial collectors. They tend to specialize in a particular geographic region and a particular set of formations known to produce good fossils: after all, they are doing this for a livelihood, so they need to have some likely return on their investment. In some cases, they are the best outfits able to field crews and run preparation labs in the regions they operate, although some teams might be ill-equipped or relatively unskilled (but the same can be said about some avocational and professionals...) In some cases, the commercial collectors cooperate with researchers to bring the fossils into the public trust; however, in some cases (as discussed below), there are conflicts between the goals of professionals and commercials.

Some historical commercial collectors were major contributors in the history of paleontology, such as Mary Anning (1799-1847) of England and the Sternberg Family of the western U.S. (The latter are an extension of the practice of hired crews used by the professional paleontologists: a very common practice in the 19th Century in the American West.)

Proponents of commercial collecting and sales of fossils put forth some important arguments:

(Here is a commentary taking the pro-commercial collector position).

However, others point out that there are many problems with the commercial collection of fossils:

(Here is a commentary taking the anti-commercial collection position.)

The most famous story of a conflict between commercial collectors and professional paleontologists, as well as issues of land management, Native American rights, and much more, is the case of "Sue" the Tyrannosaurus rex. In 1990 the Black Hills Institute (BHI, a commercial collecting firm operating out of Hill City, South Dakota) was exploring for fossils in the Hell Creek Formation (the latest Cretaceous of western North America) on the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. Team member Sue Hendrickson went off on her own and discovered what turned out to be the largest (at the time of discovery) and most complete (even to this day) T. rex skeleton ever found. The BHI dug up the specimen and brought it back to Hill City. However, a dispute arose: the land owner (Maurice Williams) claimed that the $5000 they had paid him was NOT for the specimen, but simply the right to prospect his land; Williams argued that the specimen belonged to him, not BHI. Because Williams is a member of the Sioux nation, this dispute became an issue of federal law. In 1992 the FBI and National Guard came to BHI and took control of the fossil. A legal decision in 1995 determined that "Sue" was indeed Williams property. The specimen went to the auction block at Sotheby's, where for $8,362,500 the Field Museum in Chicago acquired the specimen (backed by Disney and McDonalds).

(The story of "Sue" has been the focus of two different documentary: a markedly pro-Larson one from 2014, and a more balanced one by the TV series NOVA from 1997.

In the United States, fossils are generally regarded as mineral rights rather than antiquities (such as artifacts and human remains). The laws that govern them depends on the type of land concerned:

These protections don't always work, though: they have to actually be enforced. Mismanagement of Fossil Cycad National Monument in the 1920-1950s was such that people would just take away fossils from the Monument! With no more fossils to display or protect, the National Monument was decommissioned in 1957.

Other nations have different laws. In some fossils are regarded as protected antiquities or as part of the natural heritage, and are the property of the State (or the Crown), regardless of the private vs. public nature of the land they are found on. In others there are no protections anywhere except their national parks. And many nations have protections that effectively exist only on paper: big "grey" markets (really black markets, but with protection of government officials having been paid off.)

Recent years have seen the repatriation of illegally acquired fossils to the country of their origin: in particular Mongolia and China.

A particularly famous case of repatriation, however, actually removed fossils from the public trust. This is the case of Kennewick Man, an 8.9-9 ka skull discovered in 1996 from the banks of the Columbia River in Washington State. The morphology of the skull is more like a Polynesian or European than a Native American, so some paleoanthropologists suggested this was NOT from a population that arrived over Bering, but instead from some other part of the world. Local Native American tribes, however, argued that this specimen was one of their owned, and following the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) should be returned to them for burial. In 2004 the US Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit argued that the specimen was too far removed from present day to be securely related ethnically to any extant group. New DNA analysis published in 2015 did actually demonstrate the close genetic affinity of Kennewick Man to native populations of the American Northwest, so it was announced in Spring 2016 that the specimen will be repatriated.

Paleontology needs to get its information out from the lab to the public. What are the ways this can happen?

The technical literature is a traditional method, but that is really for communication of scientist-to-scientist. Public talks are equally old, and still pretty common, but are now enhanced by such things as outreach websites (like the Witmer Lab site at Ohio University.) Or there are site-based outreach, of which museums are the main method.

Of course, science news is one way, but the news media have their own agenda. Most importantly, of course, news reports are brief, but science is in the details.

The blogosphere allows for more detailed scientific information, but not sites are equally reliable or useful. Some are by professional scientists; others by highly knowledgeable science writers; but some are just by fans who might not know the professional information as well. More problematic, though, are websites by anti-scientific organizations or by people promoting fringe ideas.

What are the main "take aways" from a course like this? What should everyone in the public know about the prehistoric past? Here are my suggestions: