Key Points:

•Neornithischia is the sister-group to Thyreophora. It contains Marginocephalia, Ornithopoda, Thescelosauridae, and a series of basal forms.

•Thescelosauridae was a diverse clade of small (almost always smaller than humans) bipeds. Many of them show evidence for burrowing ability, making them sort of "dinosaurian rabbits"

•Ornithopoda was one of the most successful of all dinosaur herbivore groups. Primitive members were small obligate bipeds, but many evolved into facultative quadrupeds. Some include the largest land animals other than sauropods of all time.

•Ornithopods showed extensive modification of their chewing ability, culminating in the mobile skulls and dental batteries of Hadrosauridae.

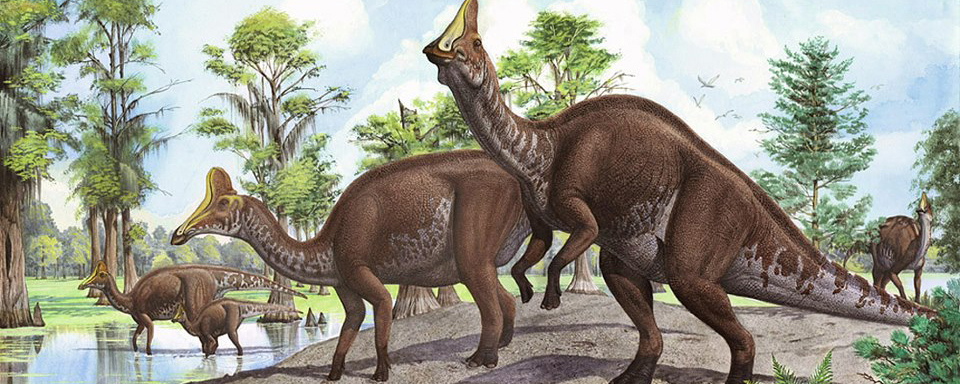

•The Hadrosauridae of the Late Cretaceous was the most speciose branch of Ornithopoda. These "duck-billed" dinosaurs are known from the entire life cycle, and from entire herds. Both major clades--hollow-crested Lambeosaurinae and broad-snouted Saurolophinae--show extensive features for some form of visual (and/or auditory) displays, suggested complex social interactions.

WHAT IS AN ORNITHOPOD? The Incredible Shrinking Ornithopoda

Traditionally, Ornithopoda ("bird feet") comprised all ornithischians that weren't stegosaurs, ankylosaurs, or neoceratopisans. Eventually, pachycephalosaurs were recognized as their own distinct clade, and psittacosaurids as ceratopsians. With the development of cladistic analysis, it was recognized that Scutellosaurus and Scelidosaurus belonged with the stegosaur-ankylosaur clade, and that Pisanosaurus and Lesothosaurus (both of which were originally called "fabrosaurs") were primitive ornithischians outside of all the other major groups.

But even at the dawn of the 21st Century, Heterodontosauridae was still generally considered as sharing a more recent common ancestor with the "hypsilophodonts" and iguanodontians than with any other group of dinosaur: thus, the heterodontosaurids were thought to be the oldest branch of Ornithopoda. More recently, however, heterodontosaurids have been recognized as splitting from other ornithischians at a very basal divergence, and thus are no closer to ornithopods than to marginocephalians or to thyreophorans. So there are at present no recognized Late Triassic or Early Jurassic ornithopods.

All ornithischians closer to the hadrosaurid Parasaurolophus than to thyreophorans form the clade Neornithischia. Neornithischians have less closely packed premaxillary teeth than in other dinosaurs, and a humerus longer than the scapula.

In recent years, most phylogenies recover a series of Jurassic forms as neornithischians outside of the thescelosaurid-cerapod clade Pyrodontia. Some of these have only been described very recently, and as their anatomy becomes better known we should be better resolution of the relationships among early ornithischians. Chinese Pulaosaurus is known from a nearly-complete skeleton, and Thailand's Minimocursor nearly so. Other basal neornithischians include Middle Jurassic Chinese Agilisaurus, Hexinlusaurus, and four meter long Yandusaurus. There are small ornithischian fossils from the Late Jurassic western North American Morrison Formation referred to by some as Nanosaurus, but formerly called by a number of names, including Othneilia, Laosaurus< and Othneilosaurus. However, a recent review found that the holotype specimens for all these names are undiagnostic, and that some of these specimens are likely juveniles of larger contemporary forms like Dryosaurus. Enigmacursur does appear to be a diagnostic basal neornithischian from the Morrison, and there are as-yet unpublished specimens which might represent others.

So what IS an ornithopod, then? Ornithopoda is defined as Parasaurolophus and all taxa closer to it than to Triceratops. The latest studies (from 2020 onward) have tended to find either re-expanded Ornithopoda to include most of the classic "hypsilophodont"-grade (i.e., non-iguanodontian) ornithopods or versions where Thescelosauridae (among others) are excluded from Cerapoda; the latter is what we are following here.

THESCELOSAURIDAE

Thescelosauridae is a clade of Cretaceous bipedal forms, generally smaller than an adult human being. Thescelosaurids share fused premaxillae, expanded scapulae, and a series of other adaptations. Some members of Thescelosauridae were once united in their own clade "Jeholosauridae". There are two major clades of thescelosaurids. Orodominae is a clade of small Asian and North American forms, including burrowing Oryctodromeus and Zephyrosaurus of the Early Cretaceous of western North America, Koreanosaurus of the Late Cretaceous of (not surprisingly) Korea, Late Cretaceous North American Orodromeus, among others. Thescelosaurinae includes Early Cretaceous Chinese Yueosaurus, Changmiania, and Jeholosaurus, and Late Cretaceous Chinese Changchunsaurus and Haya. These form a paraphyletic grade relative to the Late Cretaceous North American Parksosaurus and long-snouted latest Cretaceous western North American Thescelosaurus.

The anatomy of thescelosaurids (particularly their powerful scapulae and other features of their limbs; fusion of the premaxillae to help shovel dirt; a highly increased sense of smell; etc.) suggest that many of these are powerful burrowers. In some oryctodromines there was a special articulation between the pubis and the sacrum which might have helped reinforced their pelvis when using it to brace the body while digging. Oryctodromeus was actually found preserved in its burrow, and Koreanosaurus is found associated with burrows as well. Thescelosaurids might have been the dinosaurian equivalent of rabbits or gophers: (relatively) small, numerous burrowing herbivores.

MAJOR GROUPS OF ORNITHOPODS

The marginocephalian-ornithopod clade Cerapoda is characterized by:

Early Middle Jurassic Siberian Kulindadromeus has recently been recognized as the sister taxon to Cerapoda. It is a noteworthy animal: not so much in terms of its skeleton (which is boringly standard for a neornithischian), but for its behavioral evidence and integument. Firstly it was found in bonebeds of many dozens of individuals, so it is very likely it lived in groups. More interesting than that, though, is its body covering. It is found in an environment which fine details can be preserved. It has some parts of its body (bottoms of the feet) there are simple scales; on the front of the legs and on top of the tail are more plate-like scales; on other parts of the body are simple filaments; and then there are odd plates with fuzz coming off them (unlike any structure known in other dinosaurs). So small ornithischians show complex types of integument beyond scales (and beyond fuzz).

We'll cover Marginocephalia next lecture. Now, onto Ornithopoda proper.

Ornithopods have a jaw joint ventral to the dentary tooth row, giving them a more specialized bite. (Derived heterodontosaurids independently evolved this trait.) Also, the shaft of their ulna is somewhat bowed. Additionally, ornithopods have a more complex chewing (grinding of upper teeth against lower ones) than other dinosaurs. A hinge is present between the premaxilla, upper part of the jaws, and braincase on the one side and the maxilla and bones of the cheek region on the other. It was once thought that this had a simple out-and-back motion to help grind the teeth while chewing. As we will see below, however, the motion is more complex. In any case, even early ornithopods seem to be able to grind up their food to a finer degree than most dinosaurs, allowing them to more quickly nutrients from that food.

(A note on the name "Ornithopoda": advanced iguanodontians do indeed have three-toed feet something like birds, as seen in these tracks. But basal ornithopods have four forward-facing toes, and no ornithopod seems to have the backwards-facing digit I of birds. In fact, it is kind of a lousy name for the clade, but rather late in the game to change it...)

Early Cretaceous Hypsilophodon was one of the first discovered ornithopods other than Iguanodon and the hadrosaurids, and for a long time it, "Nanosaurus", and Dryosaurus were the only known small-bodied ornithischians. It forms a clade Hypsilophodontidae with Spanish Gideonmantellia.

IGUANODONTIA

All the remaining ornithopods form a clade Iguanodontia. The members of Iguanodontia were transformed from their "hypsilophodont" cousins by a number of features:

All retained some bipedal ability, but many of the iguanodontians were facultative bipeds only, spending a sizable fraction of time on all fours.

The oldest iguanodontian known is the Middle Jurassic dryosaurid Callovosaurus. Iguanodontians become more common in the Late Jurassic, but really come into their own in the Cretaceous. In many ecosystems the iguanodontians are the most abundant large animals, displacing sauropods and stegosaurs.

The first major branch of iguanodontians is the deep-skulled Rhabdodontomorpha. It contains two major branches. Tenontosauridae is a North American clade of Early-to-earliest Late Cretaceous forms including small Convolvosaurus, intermediate-sized Iani, and larger Tenontosaurus. Their sister taxon is the Late Cretaceous European Rhabdodontidae, including Zalmoxes.

The remaining iguanodontians are the Euiguanodontia, in which metatarsal I is greatly reduced (and thus the foot is tridactyl). One branch of euiguandontian is the Southern Hemisphere Elasmaria. South American (Talenkauen, Notohypsilophodon, Anabisetia, and Macrogryphosaurus, among others), Antarctic (Trinisaura), and Australian (Weewarrasaurus, Atlascopcosaurus, Qantassaurus, ultra-long tailed Leaellynasaura, and others) taxa. Most elasmarians were 2-6 m long. Large (7-8 m long hook-snouted Early Cretaceous Australian Muttaburrasaurus has recently been found to to be an elasmarian rather than a rhabdodontoid, so that means essentially all non-hadrosaurid Cretaceous Gondwanan ornithopods were members of Elasmaria.

The remaining euiguanodontians are the clade Dryomorpha. The oldest known branch, and the one with the smallest body sizes, are the Middle Jurassic-to-Early Cretaceous Dryosauridae, best known from as Late Jurassic American Dryosaurus, African Dysalotosaurus (once thought to be the same genus as Dryosaurus), European Eousdryosaurus, and Early Cretaceous Valdosaurus of Europe and Elrhazasaurus of Africa.

The remaining dryomorphs are the Ankylopollexia. The oldest and most primitive of these are the Late Jurassic, very likely paraphyletic, "Camptosauridae". Camptosaurus itself is the best known example of these, with several other taxa (Uteodon of North America and Cumnoria and Draconyx of Europe) either as separate species of Camptosaurus or a grade of near- and early styraosternans

The remaining ornithopods form the specialized Cretaceous clade Styracosterna. Their snouts have become longer and broader-ended with a better developed grinding jaws, while their hands have become better adapted for absorbing weight. These transformations are more fully developed in the hadrosauriforms.

STYRACOSTERNA

This represents the clade comprised of Hadrosauridae and all taxa closer to hadrosaurids than to Camptosaurus. The primitive styracosternans were once all grouped together as "Iguandontidae", at least some of the old "iguanodontids" turn out to be paraphyletic with respect to hadrosaurids. Styracosterna is by far the most successful radiation among the ornithischians.

Styracosternans show the following transformations from the ancestral state:

The combination of their great size, ability to walk on their hindlegs or all fours, and powerful beaks with grinding teeth allowed styracosternans to be excellent browsers of both low and high vegetation. At least some seem to have lived in herds.

Styracosternans are known from most of the Cretaceous world, but are most particularly common or diverse in Europe, North America, Asia, and (in the Early Cretaceous) northern Africa. Among the diversity of Early Cretaceous styracosternans are:

At least some (but not all) recent studies do support a monophyletic Iguanodontidae (after a decade or so when this cluster of dinosaurs were a paraphyletic series with respect to Hadrosauridae, which to be fair is still the result of other recent studies). Iguanodontids were a successful group of large-bodied Early Cretaceous ornithopods. Nearly all have a very prominent thumb spike (but to be fair, so do more basal styracosternans.) Among the iguanodontids currently recognized are:

One subset of styracosternans (Hadrosauria) in particular shows a series of transformations including an increase in the number of tooth positions in the jaws and expansion of the snout. These dinosaurs are on the lineage which leads to the duckbilled dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae). Among the precursors and cousins of the hadrosaurids are Early Cretaceous tall-snouted Altirhinus of Asia (once considered a species of Iguanodon, Gongpoquansaurus and Probactrosaurus of China; Eolambia of western North America; Early-to-Late Cretaceous Protohadros of western North America; and Late Cretaceous Bactrosaurus and Plesiohadros of Asia. (These latter two fall out within Hadrosauridae proper in some analyses). There are many others, and more are being named every year.

HADROSAURIDAE

True Hadrosauridae is the most speciose and specialized branch of the ornithopods. All known members of Hadrosauridae proper are from the Late Cretaceous. Although known from Europe, South America, and Antarctica, the main diversity of hadrosaurids is in Asia and North America.

The transformations of hadrosaurids relative to their ancestors include:

Hadrosaurids see the fullest expression known of the ornithopod grinding mechanism. As mentioned above, it was once thought that the motion was relative simple: the side unit would move outwards when the lower jaw was brought up, giving a side-to-side grinding of the teeth during chewing. This model (proposed during the 1980s) was called "pleurokinesis" (or "side-motion"). Here is a video of a computer animation of this interpretation:

However, more detailed study using CT scans and more complete computer models show the motion is really a LOT more complex. Pleurokinesis plays a part in it, but there are other directions as well. No name is given at present for this form of jaw mechanics, but below is a preliminary model of how it works:

But wait! There's more (or perhaps "less", in terms of motion). Even more recent study suggests that motion at the joints above was limited at best. Instead, these studies suggest that the maxillae and other facial bones remained fixed in position, but that the mandible moves either by rotation along the long axes (pivoting at the predentary) and/or moving forward and backwards. Here is an animation showing one example of this:

Their exceedingly-complex tooth form--which were made of six different tissue types, rather than the standard two of most tetrapods--maintained a good girding surface as they wore down.

Hadrosaurids include some definite herd dwellers. The entire life cycle of hadrosaurids is preserved: nests, eggs, embryos, hatchlings, juveniles, subadults, and adults. Hadrosaurid footprints and isolated hadrosaurid teeth are among the most common Late Cretaceous fossils of North America. Skin impressions and even mineralized soft tissue are known for duckbills.

The latest on-going phylogenetic analyses show two major subclades of Hadrosauridae: crested Lambeosaurinae and broad-snouted Saurolophinae. The latter group has sometimes been called "Hadrosaurinae", because older analyses found Hadrosaurus of New Jersey to be a member of this group. However, most recent studies find that Hadrosaurus, Eotrachdon of Alabama, Italian Tethyshadros, and Telmatosaurus of Romania lie outside the Lambeosaurinae-Saurolophinae clade (Euhadrosauria) (However, a note of caution: some preliminary studies suggest that "hadrosaurines/saurolophines" may be paraphyletic with respect to Lambeosaurinae). Both the major clades are known from a great number of excellent skeletons.

Lambeosaurines are characterized by a hollow crest covering the nasal passage. These crests, which vary between species, may have had both a visual and sound display function. Baby lambeosaurines lacked this structure.

CT scans allow for the pathways of these passages to be studied in greater detail:

Differences in crest size and shapes within some populations may reflect sexual and/or ontogenetic variations.

Among the better known lambeosaurines are Nipponosaurus, Olorotitan, Tsintaosaurus, and Charonosaurus of Asia and Parasaurolophus, Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Velafrons, Lambeosaurus, Tlatolophus and GIGANTIC Magnapaulia of North America. Lambeosaurines are also found in Europe (such as Pararhabdodon and Arenysaurus), and a member of this European branch (Ajnabia) made it to northern Africa.

Saurolophines (aka "hadrosaurines") differ from their relatives by greatly flared snouts and greatly expanded nares. Some saurolophines had (relatively) short snouts: North American Gryposaurus and Brachylophosaurus, for instance. Others had longer snouts: North American Maiasaura and Prosaurolophus and transcontinental (Asia and North American) Saurolophus. The extreme development of the duckbill can be found in the the Edmontosaurini, a group containing sauropod-sized Shantungosaurus (largest of all ornithischian dinosaurs) of China, Kamuysaurus of Japan, and North American dwarf Ugrunaaluk (which is possibly just Edmontosaurus) and large (but not quite as big as Shantungosaurus) Edmontosaurus proper and species sometimes considered separate genera (Anatosaurus and Anatotitan), but generally all considered Edmontosaurus. (There is recent work to show that there are only two species, each with different growth stages: personally, I am fine using the old name Anatosaurus for the geologically-younger annectens, but am willing to follow the common usage and call them all "Edmontosaurus".) Babies of even the long-snouted saurolophines had relatively short faces.

Both saurolophines and lambeosaurine produced giants of greater than 13 m in length. These represent the largest animals other than sauropods that have ever lived on land, and the heaviest bipeds in Earth's history.

Microwear analysis of the teeth of hadrosaurids is consistent with their complex chewing patterns. In at least the broad-billed edmontosaurs there is a great degree of scratching on the teeth, suggesting that they were primarily low browsers of tough vegetation ("grazers"). (Given the wide snouts of Edmontosaurus, Shantungosaurus, and so forth, this makes a lot of sense.) Studies have not yet been published to see if most hadrosaurids were primarily low browsers, or if some of them might have been mostly high browsers. Given the diversity of bill shapes and snout lengths (and the diversity of species overall), there was probably a number of different diets among the hadrosaurids.

EVOLUTIONARY PATTERNS IN BASAL NEORNITHISCHIA & ORNITHOPODA

Feeding adaptation transformations:

Locomotory changes:

Social behavior in Ornithopoda:

Neornithischians (in particular ornithopods (in particular iguanodontians (in particular hadrosaurids (in particular lambeosaurines)))) have abundant evidence for socially-related adaptations, including: herding; visual (and possibly aural) displays; species recognition structures; possible sexual dimorphism. We will discuss these

more fully in the third section of the course.

Heterochrony, size, and ornithopod history:

In general, peramorphosis seems to play an important role in neornithischian evolution. Hatchling iguanodontians tend to resemble adult "hypsilophodonts", while hatchling hadrosaurids tend resemble young primitive iguanodontians, and young hadrosaurids tend to resemble the immediate outgroups of Hadrosauridae.

Basal neornithischians and basal ornithopods were small (comparable to basal members of other ornithischian groups). But at the base of Iguanodontia and the base of Styracosterna there are major size increases. Additionally, various different styracosternan lineages independantly achieved very large (>12 m) size.

To Next Lecture.

To Previous Lecture.

To Lecture Schedule.